Building TubeAlert, a Serverless Progressive Web Site with push notifications

17 July 2017

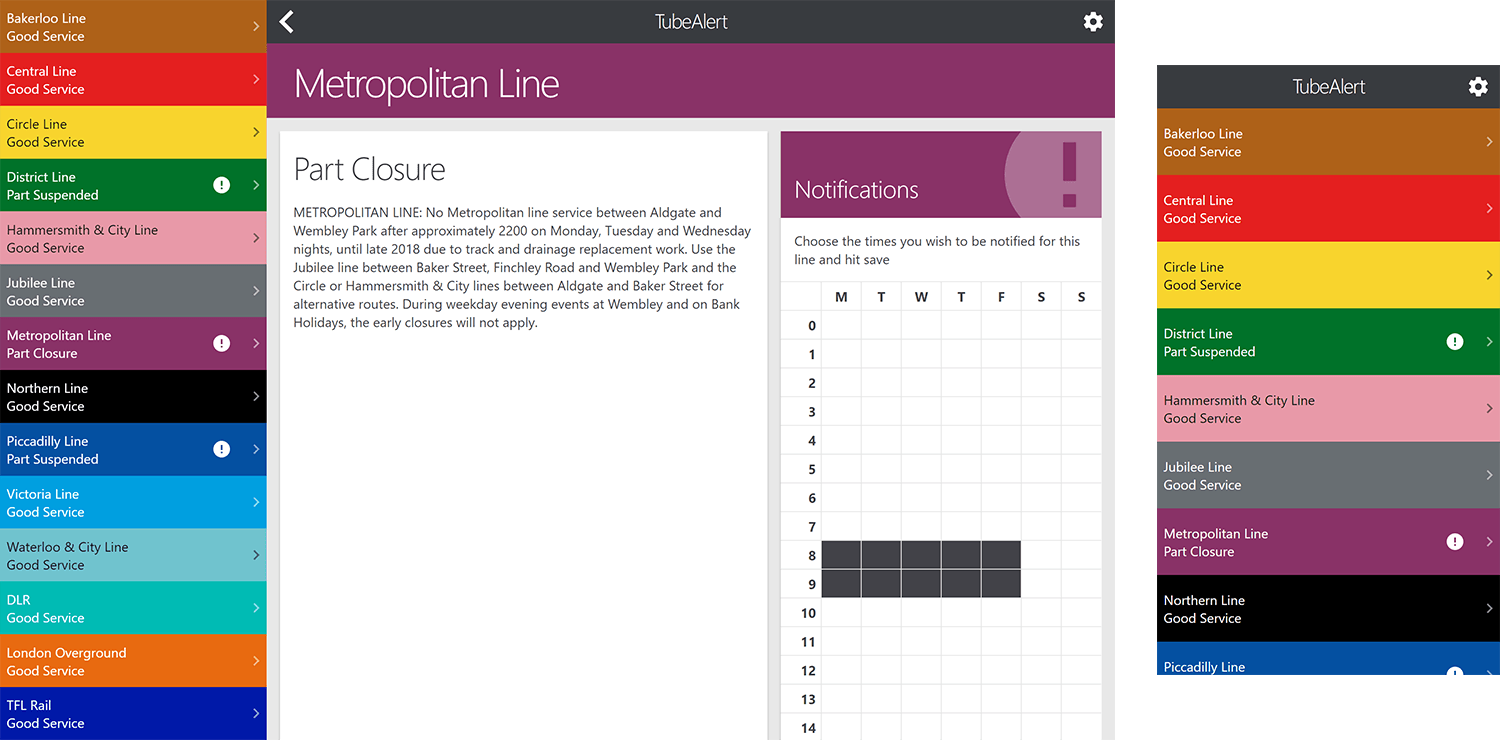

TubeAlert is a web site intended to be a quick indicator of the status of the London Underground. It has a no-nonsense interface to give the answer immediately. It also allows the user to subscribe to a tube line and time slot to be alerted to any disruptions. It is all built on the open web from a simple webpage with progressive enhancement up to full progressive web app that can be added to the home screen. The goal was to build the full feature-set as cheaply as possible. This article is a case study documenting the techniques and tactics used as well as the technologies in play such as NodeJS, React, Service worker, Webpack, Serverless, Travis, AWS Lambda / S3 / DynamoDb / Cloudformation / Cloudwatch.

All the code is on Github.

Table of contents

This is a long read, so here’s a table of contents in case you just want to skip to the parts you are interested in.

- Data source

- Goals

- Workflows

- Data model

- Infrastructure

- Building the Lambda functions (Node & Serverless)

- Building the front end (React & Webpack)

- Static assets

- Deployment pipeline

- Making it a Progressive Web App

- Push notifications

- Completion

Data source

This is all made possible because TFL have a fantastic policy of open data with a very good API. This is a great public service and enables a project such as this to exist due to offering data on the tube status, as well as many others (including Air Quality). You should take a look and see if you are inspired to build anything yourself.

Goals

Open web

This project is not intended to be a native app, behind an app store. The goal of this project is to build something on the open web using open standards, yet get much of the functionality of a native app. With service worker we can build an application that works offline, supports push notifications, and can be added to the homescreen. Those visitors that don’t want all that can still benefit from seeing a quick status update without installing anything.

Progressive Enhancement

We believe in a universal web for all. When a website is able to offer core functionality (such as raw textual information) without JavaScript then it should, responsively. The featureset should then enhance from there. The most recent tube status is available to read without JavaScript, so it works with a limited connection or even via a text based browser. Each click through will result in a full page refresh. If JavaScript successfully loads then it becomes more of a webapp, where pages load instantly without the refresh. If the browser supports Service Worker it enhances again, allowing it to work offline or be added to the homescreen (supported in Firefox, Chrome and Opera). If the browser supports web push notifications then the user will be offered the option to subscribe to alerts when the tube is disrupted.

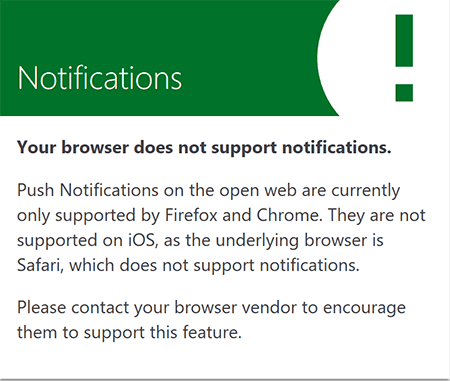

Note, usual progressive enhancement practices would mean keeping the advanced features silently away from those who can’t support it. However, we have an agenda to want the other browsers to catch up, so we encourage users to hassle their browser vendors with a notice telling them what they are missing:

Low cost

Most of the time this application wouldn’t be doing very much. Traffic is not expected to be high and notifications only need to be sent out when there is a problem. Therefore, the desire is to ensure the application runs as cheaply as possible. It cannot run as a static website as there needs to be a server-side component to fetch data from TFL and send notifications. There also needs to be a data store to store the status updates and user subscriptions.

Normally this would dictate the need for a server, but AWS offer several “Serverless” solutions. This means AWS take care of the underlying servers and instead operate API based services. With the requirements this dictates that TubeAlert will be using:

Each of these operates on a pay-as-you-go basis, and only charge for your actual usage. There are no servers sitting around under-utilised. AWS offer a generous Free tier, especially for DynamoDB and Lambda, so it is possible that the entirety of TubeAlert can function without costing anything.

Workflows

As we will be using Lambda, we need to establish the workflows that make up the featureset of the TubeAlert app. These will effectively become individual Lambda functions. There are 7 main workflows:

Fetch - Every two minutes

This needs to run on a schedule/cron job every two minutes. It is responsible for querying the TFL API to collect the latest status of the Tube Lines. It should then store that in the TubeAlert data store.

Next, it needs to compare this latest status to the previous one (from two minutes ago). If any of the lines have changed status then it needs to find any subscribers to that line at that time and notify them of the change.

Every hour

This needs to run on a schedule/cron job at the start of every hour. It is intended to notify users whose subscription window just began, that their line is disrupted. First it fetches the latest status and checks if any lines are disrupted. If so, then it finds subscriptions for that line that just started and notifies those users.

Notify

This is the actual act of notifying a user of a disruption to their line. It involves retrieving the notification data from the datastore and calling the API endpoint of the browser, as provided by the user’s subscription. It only handles one subscription at a time (but many could run in parallel). It should run in response to a new entry in the “Notifications” table.

Subscribe

This is a public endpoint at /subscribe. It allows the user to subscribe to push notifications (where supported by the browser). It accepts a POST request containing the subscription endpoint generated by the browser (UserID), and the line and times the subscription is for. It stores these subscriptions in the data store.

Unsubscribe

This is a public endpoint at /unsubscribe . It accepts a POST request with the payload being the UserID. It removes all subscriptions for that user from the data store.

Latest

This is a public endpoint at /latest. It accepts a GET request and returns a JSON response contains the latest status for every line.

Webapp

This is the public endpoint for the website itself, accepting GET requests at all remaining URLs (such as /, /bakerloo-line and /settings). It generates the server-side version of the React webapp, allowing the site to work without JavaScript and returning HTML as the output.

With these workflows decided we can look at how we can perform these tasks with the data available.

Data model

These are the five main bits of data the application is concerned with:

- Status - the current running status of a TubeLine

- TubeLine - the tube line itself

- User - a user looking to subscribe to disruptions on a line

- Subscription - said subscription for a day and time slot

- Notification - when a user is to be notified of a disruption to a line

This domain structure and the clear relationships within it would normally give rise to a relational (SQL) database, as that is what they are best at. However the cost and maintenance constraint means using DynamoDB, which is a NoSQL database, so we need to think differently about how to structure this.

In DynamoDB each table needs a Partition key. Optionally each table can have a Sort key. The Primary key is based on either just the Partition key or the combination of Partition key and Sort key. It must be unique within the table.

You can only Query for a list of items where they share the same Partition key. Query is much faster than List where you effectively read the whole table and filter in code. Therefore, in order to use Query on different data in relation to the Partition key you need to carefully design your structure and use indexes.

DynamoDB structure

With these considerations we arrive at the following DynamoDB structure:

Statuses table

This is the data from TFL (once converted into a convenient JSON schema). We store all lines for a time in a single row. This is instead of how it would be done in SQL with a single row per status for a TubeLine, which would be linked to the TubeLine table.

The Partition key is the date, such as 24-06-2017 and the Sort Key is the full timestamp, such as 1492988498. The Primary key is the combination of both, so it is unique. The most common query here will be to fetch the latest single row, so the Sort Key allows that. The last column is the full statuses information. Therefore it is not possible to query for individual line data. All lines will be fetched together.

When the application is looking for the latest status it must provide a Partition Key. For this reason we can’t simply have the timestamp be the partition key. It has to be something we can predict or calculate. This is why it has been set to the date. The query then sorts by the full timestamp descending as that is the Sort Key. There is no easy way to ask for the most recently added row for a DynamoDB table without setting it up this way.

Using the date as the Partition Key could be troublesome on the boundary of a day as the Fetch workflow needs to check the current status against the previous status. When the new day ticks over there won’t be any data coming back from the statuses query for the first try, so it won’t have anything to compare to and can’t send notifications of changes. The application will need to handle this gracefully and just ignore it for that run. However, to minimise the chances of that particular two minute window being one when a disruption occurs the date stored is actually a “TubeDate”, where anything before 3am is considered part of the day before. Most of the time the lines will be closed by 3am (and there will be few subscribers for that time) so this shouldn’t be a problem. It is an interesting limitation/quirk of DynamoDB to remember though.

Update 2020-01-04

After running for 2.5 years the Statuses table has built up a large amount of data (700,000 rows, 3.2GB). This will become a problem as the DynamoDB free tier only allows 5GB of usage.

However it is not simple to delete large amounts of rows every so often in a NoSQL world. DynamoDB supports a TTL feature which will remove rows once the timestamp value of a field is reached. Therefore we will add a new “Expiry” field for every new row (with a timestamp value set a few months in the future).

Previous rows without that field could only be removed using a long script to scan, fetch and delete rows in batches of just 25 of a time. This was going to take too long so the table was instead deleted and recreated (resulting in about 5 mins of downtime while new statuses were created). Due to this potential pain, it important to anticipate expiry of rows during the design phase as best you can.

Subscriptions table

This table stores the subscriptions that users have created. This requires the following data:

- UserID (the unique identifier generated by the users browser - usually a URL endpoint)

- Full subscription data (public keys etc)

- TubeLine

- Subscription Window (day and hours)

The UserID is set as the Partition Key. This allows a query to fetch all rows for a user, which will be used when they need to be deleted for the Unsubscribe endpoint. The Line, Day and Hour are stored as columns, along with the full subscription data.

The Sort key is a field named LineSlot. The LineSlot is a combination of the line, day and hour for a subscription. For example, a user subscribed to be alerted for the Bakerloo Line between 9am - 11:59am on Monday will have three rows in the table. For those the LineSlot columns will be:

bakerloo-line_0109 // Monday, 9am

bakerloo-line_0110 // Monday, 10am

bakerloo-line_0111 // Monday, 11am

As we can’t simply construct a large AND WHERE clause this field can be useful when looking for specific subscriptions. The application code knows which line it is looking for, as well as the date and time, so it can construct this LineSlot concept before making its search.

The Primary Key is the combination of the Partition key and Sort key, so it is unique as a user cannot have two subscriptions for the same time on the same line.

However, you cannot query a DynamoDB table by the Sort key. In our workflow such a query would be required as the application code will need to be able to find all users that are subscribed to the disrupted line for the time in question. In order to support this query we need to add a Global Secondary Index. They are effectively like a new table (and are provisioned/billed as such), but will contain the same data as the main table and crucially allow you to switch the Partition key to another column. This Partition key does not need to be unique.

Therefore, we will add an index named Index_LineSlot to the Subscriptions table, with the new Partition key being the original LineSlot. Now we can query for all rows with the same LineSlot and get back which users they are.

Another useful column is WindowStart. Every hour of a user’s subscription is stored as an individual row in the table. This means that the Hourly function, which notifies users whose subscription just started, would not be able to find the pertinent subscriptions. It would end up notifying users for every hour during their subscription. Therefore, the WindowStart column is added. This way the Hourly function can find them with a Filter on the Query. Note, a Filter on the Query does not improve performance over asking for the list without a Filter as it happens after the main query. But it does reduce the amount of data coming back from DynamoDB and negates the need for your application to do said filtering.

An example query for the Hourly function: the Circle Line became disrupted on Tuesday at 09:30am. User A has a subscription from 09:00 - 11:00, so they were notified immediately. User B has a subscription from 10:00am, so at 10:00 we want to notify User B the Circle Line is disrupted, but not User A because they already know about it. Therefore, the application can query the Index_LineSlot for

{

TableName: 'Subscriptions',

IndexName: 'index_lineSlot',

KeyConditionExpression: 'LineSlot = circle-line_0210',

FilterExpression: 'Window = 10'

}

Without the FilterExpression both UserA and UserB would have been selected. But with the FilterExpression we can be sure only UserB was alerted as desired.

Here is a sample of the results with all the columns in place:

Notifications table

This is a list of notifications to be sent. The Notify lambda function can be hooked up to trigger whenever a new row is entered here. This Lambda function will read the contents of the notification and once it has finished sending it, it will delete the row. During normal functioning therefore this table should be empty. There is never a need to query the data in this table, so the Partition key can just be a randomised string. That is then used as the Primary key.

By sending notifications to this table rather than sending them directly from the initial script we can handle many in parallel. If, for example there were 100 people subscribed to the Central Line at the same time, the Fetch command would likely timeout trying to call those APIs 100 times. Instead, it can batch input 100 rows into the Notifications table, and they can be sent asynchronously by the Notify function that subscribes to this table.

With these table structures we should be able to cover all the workflow requirements. The User table from the domain diagram hasn’t been replicated. There has not been a need to store the users separately as we don’t need to change user data independently of where it was used. This is usually the main use case for SQL. If we stored data such as a user Name which could be updated independently of the subscriptions, then we would need a relational database otherwise we have to crawl all of the subscription rows to update it everywhere.

The same principle applies to TubeLine entities. They change so rarely that the Name, Colour etc can be stored as constants in the application code rather than being stored and referenced in the data store. This table therefore isn’t needed.

The Notification table doesn’t need its relationships as the data is quickly in and out, so each row can contain all the data it needs. There is no risk of it going out of date.

The Statuses table no longer stores individual data for each line, but instead has all lines in each row. Therefore that no longer needs its relationships either.

Both SQL and NoSQL would work for this application. SQL is simpler, and would easily scale to requirements. But the Serverless aspect of DynamoDB is a big draw.

Infrastructure

Taking the data model and workflow requirements into consideration the following architecture is used.

This is the infrastructure required to satisfy the requirements and workflow. AWS is the platform hosting all the components in the application.

First of all we have DynamoDB, which has three tables (one with an extra index). This is the datastore for the application as a whole.

AWS Lambda is responsible for running the application code, and consists of 7 functions to match the workflows. The TFL fetch function queries the TFL API, and the Notify function calls Browser push notification endpoints.

AWS Cloudwatch automatically offers several metrics for its Serverless services, so we can monitor the DynamoDB and Lambda performance there.

Four of the Lambda functions are triggered via a HTTP request from a user. In order to do that we need to setup AWS API Gateway. The https://tubealert.co.uk DNS will need to be setup to point at the API Gateway, so that it can invoke the Lambda functions.

Two S3 buckets are setup. One is internal, which is used to host the code of our Lambda functions. The other bucket is public for the website static assets, such as CSS and JavaScript, and is accessed by the browser.

Building the Lambda functions (Node & Serverless)

All code for the application can be found on Github.

There will be 7 Lambda functions, but most of them will share a lot of base code. Therefore we want to actually make the whole thing one application with multiple entry points.

The application will be built using JavaScript on Node 6 (as supported by Lambda), with ES2015 syntax.

We are going to use the Serverless Framework to build the application, as it offers several features that we will come to rely on. For starters, it can create individual lambda functions for us and have them point to methods within a handler.js file, as well as setting up the triggers for them.

These are declared using yml. For example, we can setup the functions that are triggered by time in the serverless.yml file:

fetch:

handler: handler.fetch

events:

- schedule: rate(2 minutes)

hourly:

handler: handler.hourly

events:

- schedule: cron(1 * * * ? *)

These specify the handler for each Lambda function. Therefore, we can declare them within the same file (handler.js):

const Controllers = require('./src/DI').controllers;

// handlers

module.exports = {

latest:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.status(cb).latestAction(),

subscribe:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.subscriptions(cb).subscribeAction(evt),

unsubscribe:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.subscriptions(cb).unsubscribeAction(evt),

fetch:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.data(cb).fetchAction(),

hourly:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.data(cb).hourlyAction(),

notify:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.data(cb).notifyAction(evt),

webapp:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.webapp(cb).invokeAction(evt),

};

Note, all 7 handlers are in here. This is what the Lambda function will call when it is invoked. From this point on the code doesn’t know it is a Lambda function. The input was an event (evt) and the application will end when the callback function (cb) is called. These parameters are passed down to the Controllers as parameters. TubeAlert is using the concept of Dependency Injection (DI). You can see the DI container being imported at the top:

const Controllers = require('./src/DI').controllers;

This file is responsible for all of the require statements, and setting up initial parameters. Each of the Controllers is called from here, and inject any models that Controller needs (which are also dependency injected).

const getDataController = callback => new DataController(

callback,

AWS.DynamoDB.Converter.output,

getDateTimeHelper(),

getStatusModel(),

getSubscriptionModel(),

getNotificationModel(),

console

);

This methodology makes the application easy to unit test, as each file does not break out of its scope and you can mock the inputs. Third party libraries are as follows:

const AWS = require('aws-sdk');

const Moment = require('moment-timezone');

const WebPush = require('web-push');

The AWS SDK is necessary for communicating with DynamoDB. Moment is a very useful library for performing date and time calculations. Web Push is handy for abstracting the complexity of sending push notifications (as it involves encryption).

The DI container fetches some information out of environment variables, which can be setup for a Lambda function, and uses them to initialise some config that can be passed into models

const documentClient = new AWS.DynamoDB.DocumentClient({ region: 'eu-west-2' });

const config = {

TFL_APP_ID: process.env.TFL_APP_ID,

TFL_APP_KEY: process.env.TFL_APP_KEY,

STATIC_HOST: process.env.STATIC_HOST,

};

WebPush.setGCMAPIKey(process.env.GCM_API_KEY);

WebPush.setVapidDetails(

`mailto:${process.env.CONTACT_EMAIL}`,

process.env.PUBLIC_KEY,

process.env.PRIVATE_KEY

);

Models

Status model

The Status model is responsible for fetching Line Status data from TFL and storing it in the Statuses DynamoDB table. The fetchNewLatest method makes a HTTP request to TFL for the line data.

fetchNewLatest() {

const now = this.dateTimeHelper.getNow();

const url = 'https://api.tfl.gov.uk/Line/Mode/tube,dlr,tflrail,overground/Status' +

`?app_id=${this.config.TFL_APP_ID}` +

`&app_key=${this.config.TFL_APP_KEY}`;

this.logger.info('Fetching from TFL');

// only include this require on invocation (so the memory is cleared)

return require('node-fetch')(url) // eslint-disable-line global-require

.then(response => response.json())

.then(this.mutateData.bind(this))

.then(data => this.storeStatus(now, data));

}

Note how require('node-fetch') is embedded inline rather than being declared at the top. This is unusual, but has been done so that the node-fetch client does not hang around beyond the end of the HTTP request. See “Note about Lambda containers” for an explanation for why that was done, though there is likely a way to refactor it out.

Once the data is fetched from TFL it is mutated into the format recognised by the application and stored in DynamoDb:

storeStatus(date, data) {

const tubeDate = this.dateTimeHelper.constructor.getTubeDate(date);

const params = {

TableName: TABLE_NAME_STATUSES,

Item: {

TubeDate: tubeDate,

Timestamp: date.unix(),

Statuses: data,

},

};

this.logger.info(`Storing data for ${tubeDate}`);

return this.documentClient.put(params).promise()

.then(() => data);

}

This creates a single row in the Statuses table with the keys required. The getTubeDate method in the DateTimeHelper calculates the day threshold for 3am as discussed earlier:

static getTubeDate(momentDate) {

const date = momentDate.clone();

const hour = date.hours();

if (hour <= 3) {

// the tube date is yesterday

date.subtract(1, 'days');

}

return date.format('DD-MM-YYYY');

}

The getAllLatest method is able to retrieve data back out of the DynamoDb table:

getAllLatest(date) {

const tubeDate = this.dateTimeHelper.constructor.getTubeDate(date);

this.logger.info(`Getting current status for ${tubeDate}`);

const params = {

TableName: TABLE_NAME_STATUSES,

Limit: 1,

KeyConditionExpression: '#date = :date',

ExpressionAttributeNames: {

'#date': 'TubeDate',

},

ExpressionAttributeValues: {

':date': tubeDate,

},

ScanIndexForward: false,

};

return this.documentClient.query(params).promise()

.then((result) => {

if (result.Items.length > 0) {

return result.Items[0].Statuses;

}

return [];

});

}

This sets up the “TubeDate” as before and queries the Statuses table using that as the Partition key. The Sort key is the timestamp, but we don’t need to see the value of it. We just order by it descending with ScanIndexForward: false and just get the very latest with Limit: 1.

Having retrieved the latest status with all the lines it is also possible to filter that to just the disrupted lines (needed by the hourly workflow):

getLatestDisrupted(date) {

return this.getAllLatest(date)

.then(statuses => statuses.filter(line => line.isDisrupted));

}

Subscription model

The Subscription model is responsible for adding, removing and retrieving rows from the Subscriptions table.

The subscribeUser method creates the neccessary input for DynamoDB:

subscribeUser(userID, lineID, timeSlots, subscription, now) {

// process the time slots

const slots = new this.TimeSlotsHelper(timeSlots);

// create the PUT items

const puts = slots.getPuts(subscription, lineID, now);

this.logger.info(`${puts.length} puts`);

// find out any that need to be deleted

return this.getUserSubscriptionsForLine(userID, lineID)

.then((data) => {

const deletes = slots.getDeletes(data);

this.logger.info(`${deletes.length} deletes`);

return deletes.concat(puts);

})

.then(requests => this.batchWriter.makeRequests(requests));

}

A user subscribes to one tube line at a time, with a collection of days and hours. Any hours that were previously in their subscription but missing in the update need to be removed from the Subscriptions table. In DynamoDB you can only delete a single row per operation and it must be deleted by Primary key. For our Subscriptions table the Primary key is the combination of Partition key (UserID) and Sort key (LineSlot). We cannot use a DELETE WHERE clause, so we need to first fetch all the rows for UserID in order to determine those Primary key values.

getUserSubscriptions(userID) {

const params = {

TableName: TABLE_NAME_SUBSCRIPTIONS,

KeyConditionExpression: '#user = :user',

ExpressionAttributeNames: {

'#user': 'UserID',

},

ExpressionAttributeValues: {

':user': userID,

},

};

}

The TimeSlotsHelper is responsible for calculating the difference between the old subscriptions and new. New hours become DynamoDB PUT items:

PutRequest: {

Item: {

UserID: userID,

LineSlot: lineSlot,

Line: lineID,

Day: day,

Hour: hour,

WindowStart: start,

Created: now.toISOString(),

Subscription: subscription,

}

}

Missing hours that previously existed become DELETE items (we know the primary key from the previous getUserSubscriptions call):

DeleteRequest: {

Key: {

UserID: item.UserID,

LineSlot: item.LineSlot,

}

}

The result is an array of operations for DynamoDB. With one for every hour of the week this could be up to 168 operations in one request. If we were to loop through each of them individually our requests would likely time out. Luckily DynamoDB supports a BatchWrite operation, allowing up to 25 at one time. The BatchWriteHelper has been written to do this. It takes an array of operations and breaks it into chunks of 25 to perform a BatchWrite. If, for any reason, one of the operations failed it is put back into the list to try again. It does all this using a recursive loop.

makeRequests(requests, inputTotal) {

const total = inputTotal || requests.length;

if (requests.length === 0) {

// nothing to do. get out and return the original count

return total;

}

// can only process 25 at a time

const toProcess = requests.slice(0, MAX_BATCH_SIZE);

let remaining = requests.slice(MAX_BATCH_SIZE);

this.logger.info(`Processing ${toProcess.length} items`);

// perform the batch request

const params = {

RequestItems: {},

};

params.RequestItems[this.tableName] = toProcess;

return this.documentClient.batchWrite(params).promise()

.then((data) => {

// put any UnprocessedItems back onto remaining list

if ('UnprocessedItems' in data && this.tableName in data.UnprocessedItems) {

remaining = remaining.concat(data.UnprocessedItems[this.tableName]);

}

return remaining;

})

.then(remainingResult => this.makeRequests(remainingResult, total));

}

The unsubscribeUser method deletes all rows associated with a given UserID. As before, in order to do this it has to first fetch all the rows, so it uses the same getUserSubscriptions method.

When a Line becomes disrupted the application needs to be able to find all the subscribers that should be alerted. The getSubscriptionsForLineSlot method needs to query for this. We know the LineSlot as we calculate it from the disrupted line and current datetime, so we know the Sort Key. However, the UserID, which is the Partition Key, is the data we are looking for so we don’t have it. DynamoDB queries must have a Partition Key, so this is where the lineSlot index is used instead. In this index the LineSlot and UserID are swapped round, so we can query by LineSlot and get back rows containing the UserID values we want.

const params = {

TableName: TABLE_NAME_SUBSCRIPTIONS,

IndexName: 'index_lineSlot',

KeyConditionExpression: '#line = :line',

ExpressionAttributeNames: {

'#line': 'LineSlot',

},

ExpressionAttributeValues: {

':line': lineSlot,

},

};

Notification model

The Notification model is responsible for handling notifications in DynamoDB as well as sending the notifications out to the user.

Having decided which Subscriptions are to be notified the application will call createNotification for each. This method will construct a row in the Notifications table via PUT

PutRequest: {

Item: {

NotificationID: notificationID,

Subscription: subscription,

Payload: JSON.stringify({

title: lineData.name,

body: lineData.statusSummary,

icon: this.config.STATIC_HOST + this.assetManifest[`icon-${lineData.urlKey}.png`],

tag: `/`,

}),

Created: this.dateTimeHelper.getNow().toISOString(),

},

}

This DynamoDB table will be hooked up to a Lambda function that will invoke for every new row. Therefore, rows aren’t expected to last and the table isn’t intended to be queried. The Partition Key is the NotificationID, which is just a random string:

static createID() {

// generate a randomish UUID

return (`${Math.random().toString(36)}00000000000000000`).slice(2, 18);

}

The Payload is the key data that will be needed for the push notification. It is calculated here and fired into the table, so it can be processed quickly later.

The handleNotification method will have received a row from the DynamoDB table and is responsible for sending the notification and then deleting that row.

Push notifications with a payload need to be encrypted. Thankfully the web push library that we are using handles this for us, so the sending is very easy:

return this.webPush.sendNotification(subscription, payload)

.then(() => {

this.logger.info('Notification sent. Deleting record');

return this.batchWriter.makeRequests([deleteRequest]);

});

If for any reason there is a failure, AWS will try again to call the Lambda function so it takes a lot of failures for the Notifications table to not be empty nearly all the time.

Controllers

With all the data actions now available via the models, the controllers can be invoked to make use of them. They are much thinner as the models are doing the hard work, though they make heavy use of Promises as these operations must usually complete before the next begins.

As each controller is invoked by a Lambda function they are passed a callback parameter in their constructor. This came from the handler.js:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.data(cb).fetchAction()

Lambda supplies that callback function. When your application is complete you call this function to signify to AWS you are done. The callback accepts two parameters. If the first parameter is null then you signify that everything was successful:

this.callback(null, 'All done');

The second parameter is what the Lambda function will return to whatever is listening. It could be a string or an object. If there were any issues then set the first parameter:

this.callback('Failed to complete');

The contents of the parameter will be logged and the invocation will count as a failure. In many scenarios AWS (such as timed invocations) will attempt to invoke the function again a certain number of times. The callback function is passed into the constructor so it can be called from anywhere in the class to cease the operation.

Data controller

The Data controller handles the routine jobs for fetching and storing.

The fetchAction is triggered on a schedule every 2 minutes. It simply calls the StatusModel to get the latest status, and uses the NotificationModel to create a new notification row if anybody needs to be alerted to a change.

The hourlyAction is triggered on a schedule at 1 minute passed every hour. It looks for disrupted lines using the StatusModel, and looks for any subscribers to said lines using the SubscriptionsModel. If anyone need to be alerted, it’ll again use the NotificationModel.

The notifyAction is triggered via a change in the Notifications DynamoDB table. When that happens AWS will send an event in the invocation of the Lambda function. This is passed from the handler.js:

(evt, ctx, cb) => Controllers.data(cb).notifyAction(evt)

The event contains the record that changed in the table. This would include DELETE events, but we only care about new rows being entered. Therefore, if anything other than an INSERT is found the action quickly exits successfully to ignore it

if (record.eventName !== 'INSERT' || !record.dynamodb.NewImage) {

return this.callback(null, 'Event was not an INSERT');

}

Raw data from DynamoDB is not easy to parse as it is closer to being serialised. Therefore, in order to use the new record it is converted using the AWS library provided AWS.DynamoDB.Converter.output:

const rowData = this.dynamoConverter({

M: record.dynamodb.NewImage,

});

return this.notificationModel.handleNotification(rowData)

This notification is then handled by the NotificationModel.

It is possible for a user to remove their subscription from your website directly in their browser, either by blocking notifications on your website or clearing their website data. When this happens you will not be informed so the user lingers in your data store. When you attempt to send that user a notification the endpoint will respond with a 404 Not found or 410 Gone status. These need to be caught and used to remove the subscriptions from our data store.

.catch((result) => {

const statusCode = result.statusCode;

this.logger.info(statusCode + ' response code');

if (statusCode !== 404 && statusCode !== 410) {

return this.error();

}

return this.removeOldSubscription(rowData)

.then(this.done.bind(this))

.catch(this.error.bind(this));

});

Status controller

The Status controller handles an incoming GET request for /latest and returns a successful JSON response of all the lines statuses (from StatusModel), to be used by the client side JavaScript application.

The request will have come via the API Gateway, and the response will need to be readable by that. The callback is called with a standard format:

return this.callback(null, this.jsonResponseHelper.createResponse(data, 120));

This format is generated by the JsonResponseHelper which sets proper headers to render the page as JSON, as well as cache-control. These come back in an object format that API Gateway will use:

return {

statusCode: 200,

headers,

body: JSON.stringify(data),

};

Subscriptions controller

The Subscriptions controller handles the incoming POST requests for subscribe and unsubscribe. It simply calls the corresponding method in the SubscriptionModel and returns a successful JSON response in the same way as the Status Controller.

However, these POST requests will have come with data. AWS will pass the request via the event object, which can be parsed for the body.

subscribeAction(event) {

const body = JSON.parse(event.body);

const userID = body.userID;

const lineID = body.lineID;

const timeSlots = body.timeSlots;

const subscription = body.subscription;

Webapp controller

The Webapp controller handles an incoming GET request via a URL and returns a webpage.

The invokeAction takes an event which will contain the path requested. Browsers will frequently make requests for favicon.ico at the root of your domain so instead of booting the entire application to not find it, this action immediately exists successfully with a 404.

const path = event.path;

if (path === '/favicon.ico') {

return this.callback(

null,

{

statusCode: 404,

headers: {

'cache-control': `public, max-age=${60 * 60 * 24 * 60}`

},

body: 'Not found'

}

);

}

The method then fetches the latest status data and passes it into app.js, which will generate a body to be returned as text/html

const App = require('../../build/app.js'); // Load the compiled App entry point

return App.default(data, path, this.assetsHelper, body => this.callback(

null,

{

statusCode: 200,

headers: {

'content-type': 'text/html; charset=utf-8'

},

body,

}

));

The actual contents of app.js is discussed in more detail in the “Server side rendering” section.

Serverless framework

The Serverless framework is a very useful application to manage your Lambda based application.

Once installed it is configured for your application via the serverless.yml file, which has several parts.

Run an individual function

Each function is declared in the functions section and declares the handler method and trigger. The simplest form is the schedule based function:

functions:

fetch:

handler: handler.fetch

events:

- schedule: rate(2 minutes)

Functions that are powered by API Gateway are also easily setup here:

subscribe:

handler: handler.subscribe

events:

- http:

path: /subscribe

method: post

Serverless will automatically setup the API Gateway endpoints and hook them to your Lambda function.

While building, functions can be invoked locally using a command:

serverless invoke local --function fetch

There are some secrets that the application requires. These are handled via environment variables, which are declared as being used in the config:

environment:

TFL_APP_ID: ${env:TFL_APP_ID}

TFL_APP_KEY: ${env:TFL_APP_KEY}

GCM_API_KEY: ${env:GCM_API_KEY}

CONTACT_EMAIL: ${env:CONTACT_EMAIL}

STATIC_HOST: ${env:STATIC_HOST}

PRIVATE_KEY: ${env:PRIVATE_KEY}

PUBLIC_KEY: ${env:PUBLIC_KEY}

These environment variables must be set before invoking the function or it will not work.

In order to talk to AWS components, such as DynamoDB you need to have set up your AWS Credentials file by creating an ID and Secret Key in IAM.

For functions that require input (such as the subscribe/unsubscribe POST events), an input event can be provided with the --data flag, as described in the documentation.

Deploying

The serverless framework can be used to deploy your Lambda functions to AWS, rather than uploading them manually via the console. This involves zipping all of your application code and uploading it to S3 in the deploymentBucket you specifiy in your yaml. This is then used to setup the Lambda functions so need to contain all code your functions require. This means it must include your node_modules, so the deployment has to happen after npm/yarn install.

If you have a lot of application code you can find this deployment taking a very long time. To help with this you can exclude certain files from the zip. The lambda functions do not require the test suite for example, so that can be removed. Exclusions are specified in the Yaml.

package:

exclude:

- tests/**; # Lambda functions do not use the tests

- coverage # Coverage reports only needed as a development tool

- build/static/** # Lambda functions don't need built static assets

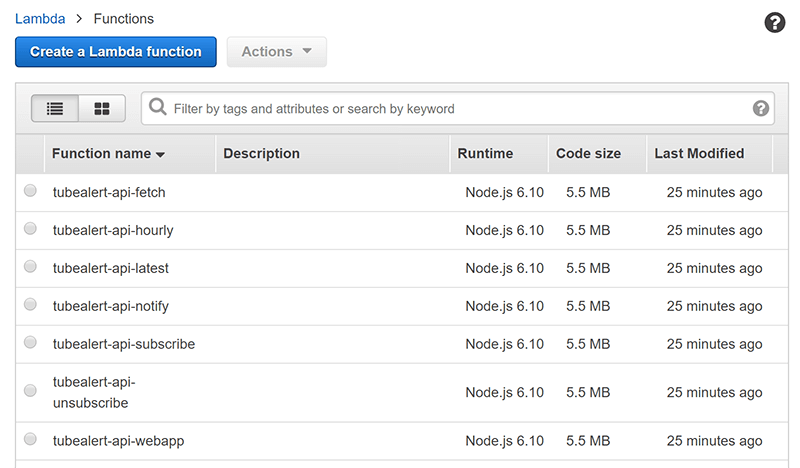

Once this deployment is complete the Lambda functions are all visible in the AWS Lambda console:

With the way we have structured the application, all the functions actually consist of the same code. They just have a different entry point each. This is why they all say 5.5MB for the code size.

As part of this deployment Serverless would have also set up the triggers for the functions. This was simple for the time based functions (fetch & hourly), but the others need more setup.

Cloudformation

TubeAlert has several parts of infrastructure to support Lambda: DymanoDB, S3, Cloudwatch and API Gateway. It is possible to set up all these parts manually in the AWS web console. However, it is much more stable and predictable if we can define that infrastructure in code. This can be done via AWS Cloudformation, which lets you declare your infrastructure using JSON or Yaml.

The Serverless framework Yaml file allows you to have a resources section, which consists of a Cloudformation template. The TubeAlert resources section sets up a few things.

Cloudwatch can be configured by this section. Every Lambda function generates logs in Cloudwatch. By default these are retained forever, which would eventually use enough space to exhaust the free tier. This application doesn’t really need to keep logs for that long so the retention time is set to 30 days for each function:

LatestLogGroup:

Type: AWS::Logs::LogGroup

Properties:

RetentionInDays: "30"

SubscribeLogGroup:

Type: AWS::Logs::LogGroup

Properties:

RetentionInDays: "30"

...

The DynamoDB tables are also set up this way. This sets up the names of the tables, Partition and Sort Key, and any indexes. It also needs to setup the provisioning. For example, for the Notifications table:

TubeAlertNotificationsTable:

Type: AWS::DynamoDB::Table

Properties:

TableName: tubealert.co.uk_notifications

AttributeDefinitions:

- AttributeName: NotificationID

AttributeType: S

KeySchema:

- AttributeName: NotificationID

KeyType: HASH

ProvisionedThroughput:

ReadCapacityUnits: 1

WriteCapacityUnits: 1

StreamSpecification:

StreamViewType: NEW_IMAGE

Note, this table also sets up the StreamSpecification to have a notification stream when changes happen on rows. NEW_IMAGE means the full contents of the row will be part of the stream items. This stream can now be used as a trigger in the Notify Lambda function setup.

notify:

handler: handler.notify

events:

- stream:

type: dynamodb

arn:

Fn::GetAtt: [ TubeAlertNotificationsTable, "StreamArn" ]

batchSize: 1

startingPosition: LATEST

Fn::GetAtt allows one part of Cloudformation to reference another part, so it links up programatically. If you didn’t use this you would need to know the Amazon Resource Name (ARN) of the stream, meaning you would have to manually create your resources in a very specific order to retrieve them one after the other.

IAM

AWS handles all security and permissions via IAM. In order to ensure our Lambda functions have read & write permissions to the DynamoDB tables we need to set that up. Serverless will automatically create an IAM Role for the Lambda functions. We must now attach permissions to that role. The structure is the same as the Cloudformation, but is added to the iamRoleStatements property in order to be linked to the Lambda Role that Serverless will generate. Each of the tables and the Notify stream are added to the yaml:

iamRoleStatements:

- Effect: 'Allow'

Action:

- 'dynamodb:*'

Resource:

# ...

- Fn::Join:

- ''

- - 'arn:aws:dynamodb:'

- Ref: 'AWS::Region'

- ':'

- Ref: 'AWS::AccountId'

- ':table/'

- Ref: TubeAlertNotificationsTable

- Fn::GetAtt: [ TubeAlertNotificationsTable, "StreamArn" ]

At present this grants the functions all DynamoDB rights for these tables, but that can be refactored to simple Read/Write permissions.

Monitoring

Monitoring for the application is handled via Cloudwatch, which has a generous free tier for logs and monitoring graphs.

Logging

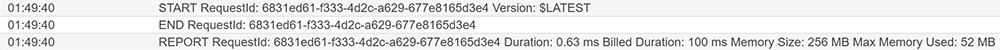

As mentioned earlier, Lambda functions will log to Cloudwatch automatically. At its simplest this will log Lambda START, END and REPORT events

The REPORT event gives you information about how time and memory the function took. This is important to check as you are billed for the amount of use.

In a NodeJS Lambda function, calls to console.info will be added to the Cloudwatch logs, so this is very useful to see the progress of the application. Error states passed to the callback function will also appear.

Graphing

Logging is useful for seeing the detail of the application as it runs, and for helping solve issues. However, to get an indication if your application is running well Cloudwatch graphs are the most useful.

AWS offer several metrics for Lambda functions. These include:

- Invocation count

- Duration

- Error count

These can be graphed with multiple functions on the same graph. For example, the graph of Lambda duration shows that the slowest function is the fetch function (which is to be expected as it does most work and makes and external API call):

The API gateway also has some metrics, such as a call count.

Multiple graphs can be put together into a Dashboard:

This is the most valuable way to see immediately how the application is performing, and has become the original way to notice when there is an issue. Once setup it very quickly highlighted an issue with the Lambda functions due to containers.

Note about Lambda containers

Lambda functions run in containers. To improve start-up performance AWS may keep the container around once your function completes. Then if you run the function again your application is already bootstrapped. You can’t guarantee it but those containers may stick around for up to 24 hours. This is particularly likely if your function runs fairly often (such as the TubeAlert Fetch function running every 2 minutes).

In Nodejs this means if you set a variable in the scope of the file, it will still be set on the next invocation. Therefore the TubeAlert DI (Dependency Injection) container was written to instantiate new objects each time the function is run, rather than creating them once at the top of the file. As an illustration:

const dateTimeHelper = new DateTimeHelper();

const statusModel = new StatusModel();

function doThing()

{

const time = dateTimeHelper.getTime();

statusModel.get(time);

}

vs

function doThing()

{

const dateTimeHelper = new DateTimeHelper();

const statusModel = new StatusModel();

const time = dateTimeHelper.getTime();

statusModel.get(time);

}

This is particularly important with DateTime, otherwise the application date will be frozen for every invocation until the container is terminated.

Another side effect is that memory leaks are a more pressing concern. During development it appeared to be the case that the longer the container lived the slower the function became, until it reached the timeout and errors prevailed. Then, occasionally, the container terminated and the cycle reset.

There was an investigation into the code to ensure no data was hanging around unnecessarily. However, libraries or processes outside of the function (such as growing log files perhaps) are out of your control.

Lambda allows you to choose an amount of memory allocated to your function. Originally this was set to 128MB for all functions. Although the logs were showing the fetch function usage as being well below that, the slowdowns and timeouts were still occurring. It seems that the underlying CPU, network and disk performance are correlated (though not declared) to your choice of memory allocation. By upping the allocation to 256MB the fetch function now sits mostly under ~1000ms. The timeout was also increased to 10 seconds but it now never reaches that. The Lambda errors graph is now mostly flat.

We can take advantage of the container behaviour though. For the latest endpoint we know that any requests within 2 minutes will be the same, as that is the rate the data is fetched from TFL. Therefore Node can store the DynamoDB result in a variable that will persist. Any subsequent calls within two minutes will reuse that data immediately, improving performance and keeping the DyanmoDB usage low.

The StatusController stores a cache object outside of the class itself

const emptyCache = {

expires: 0,

data: null

};

let statusCache = emptyCache;

Any values set to statusCache are then persisted:

statusCache = {

expires: now + (120 * 1000),

data

};

The action can check to see if this data is available and not expired. If so it just uses it straight away.

if (statusCache.expires > now) {

// cache locally if the container is still alive

this.logger.info('Data is still in cache. Using it');

return this.callback(null, this.jsonResponseHelper.createResponse(statusCache.data, 120));

}

The action does not rely on the data being in this cache, but can achieve a small bonus while the container is still alive.

Tests

TubeAlert is using Jest as the testing framework. It offers useful mocking functionality. As the TubeAlert application has been building using Dependency Injection it is very easy to test individual files.

The test for the SubscriptionModel demonstrates this. First the Model is constructed with its dependencies. However, those dependencies in this scenario are mocks, provided by Jest. Here for example we mock the DocumentClient:

const mockQueryFunction = jest.fn();

const mockDocumentClient = { query: mockQueryFunction };

const model = new Subscription(

mockDocumentClient,

mockBatchWriteHelper,

mockTimeSlotsHelper,

mockLogger

);

Then we can test that the subscribeUser method will call that client with the correct inputs:

return model.subscribeUser('userID1', 'lineID1', 'timeslots', 'subscription1', 'now')

.then(() => {

expect(mockQueryFunction).toBeCalledWith({

TableName: 'tubealert.co.uk_subscriptions',

KeyConditionExpression: '#user = :user',

ExpressionAttributeNames: {

'#line': 'Line',

'#user': 'UserID',

},

ExpressionAttributeValues: {

':line': 'lineID1',

':user': 'userID1',

},

FilterExpression: '#line = :line',

});

});

This checks that the DynamoDB will be called with the correct query, without actually making that query. Dependency Injection makes these true unit tests possible.

Building the front end (React & Webpack)

Package management

TubeAlert uses Yarn for package management. As with NPM, this uses a package.json file. We have been careful to ensure that the packages are correctly in require or require-dev as required. This is so that before live deployment any packages in require-dev can be stripped out. This makes a big difference to the Lambda functions. Without this step they are over 50MB, compared to 5MB after the purge.

App initialisation

The application is built using React and Redux, utilising JSX and ES2015 syntax. Therefore, in order to be recognised by the browsers these need to be compiled using Babel.

CSS for the application is written using Sass, so this also needs to be compiled.

In order to do this compilation Webpack was chosen. The client side React application begins with an entry point, which is client.js. In this file, the application initialisation happens:

if (window.fetch) {

init(4); // version number

}

The window.fetch check is a “Cutting the mustard” check. The client side application will only activate in browsers that support fetch. Other browsers remain on the server rendered version of the site requiring full refreshes to change page. This requires Server Side Rendering which we’ll talk about later, and is key to the Progressive Enhancement goal. It means that older browsers can still get the core functionality and we don’t have to painstakingly work on backwards compatibility.

const savedLines = getLines();

if (savedLines.length > 0) {

// read the saved lines and go and fetch newer asynchronously

store.dispatch(readLines());

} else {

// first time visit, use the embedded data (save a second call)

const lines = JSON.parse(document.getElementById('js-app-bundle').dataset.lines);

store.dispatch(setLines(lines));

}

The first thing the application does in the init function is check for the existance of TubeLine status data in LocalStorage. In order to facilitate Offline viewing later, we need to store the website data somewhere. Therefore it is stored in LocalStorage and retrieved immediately on application start.

If data was found in LocalStorage it is dispatched to the Redux store readLines action. This action will read the data out of LocalStorage first of all and allow the application to build.

export const readLines = () => (dispatch) => {

dispatch(receiveLinesUpdate(getLines()));

dispatch(fetchLines());

};

Obviously, the data in LocalStorage will get out of date very quickly so a call to fetchLines is dispatched. This makes a call to the /latest endpoint and updates the application from the result (as well as updating the data in LocalStorage).

If there was nothing in LocalStorage then this is likely your first visit to the website. In this scenario the application starts using the Line status data that was embedded in the webpage which came from the server. This allows the page to render instantly without waiting for completion a second HTTP call, off to the /latest endpoint.

This means there are three different places the initial data for the application can come from: LocalStorage, the /latest endpoint, or the embedded JSON. The application will also make a call to /latest every two minutes while the window is open to ensure it remains up to date. This is the main reason Redux was chosen as a technology. With Redux the application doesn’t have to care where the data is coming from. When it arrives from any source it dispatches an event and the application updates.

Now that the application has data it can start up React. The template provided by the server will have an element that can be targeted by ReactDom (<div id="webapp"></div>):

ReactDOM.render(

<Provider store={store}>

{Routes}

</Provider>,

document.getElementById('webapp')

);

<Provider> is the Redux wrapper. The first part of the Application to render is of course Routes

Routing

TubeAlert is using React Router (v3). There are only three routes to worry about:

- Home

- Line

- Settings

They all share the same base view so they are under the same Route path.

const routes = (

<Router onUpdate={handleUpdate} history={history}>

<Route path="/" component={BaseContainer}>

<IndexRoute name="index" component={Index} />

<Route name="settings" path="/settings" component={SettingsContainer} />

<Route name="line" path="/:lineKey" component={LineContainer} />

</Route>

</Router>

);

When the application is being run in a browser we want the URL to update as you change view, without a full page refresh. This is achieved with the browser History API. React router supports this as the browserHistory object. We would want to use that with history={browserHistory}, but that isn’t supported on the server. The application checks to see if it’s on the server, and sets the history variable as appropriate. It does this by checking for the presence of the window object, which will only exist in the client browser.

const isBrowser = (typeof window !== 'undefined');

const history = isBrowser ? browserHistory : null;

If we are on the server then the history object will be set to null, as we don’t need history to be supported for a single request->response action. When in the browser React router will also handle clicks of the back button. Due to the way the page is designed this action feels more correct if the view is taken back to the top of the page on each transition. onUpdate has a handler to achieve this.

const handleUpdate = () => {

if (isBrowser) {

window.scrollTo(0, 0);

}

};

Containers

The React application is setup with Stateless Functional Components. With this methodology the hard work and state calculations happen in a Container, and the view Component itself is a pure JavaScript object that accepts props and builds the HTML view.

Therefore, the routes call the appropriate Container classes. The BaseContainer is a wrapper around the whole application and handles data common to all views. As all views contain the list of all lines, this is where that data is processed.

The export of the BaseContainer class is wrapped in the Redux connect method:

export default connect(

storeProp => ({

lines: storeProp.linesState.lines

})

)(BaseContainer);

This allows the Redux store to provide the line data that will be used. When being loaded on the client side, the application will need to poll for new data every 2 minutes.

componentWillReceiveProps(nextProps) {

if (this.props === nextProps ||

!this.allowPolling

) {

return;

}

window.clearTimeout(this.timeout);

this.timeout = window.setTimeout(

() => store.dispatch(fetchLines()),

1000 * 60 * 2

); // poll every two minutes

}

The window.setTimeout function will not work server side, as there is no window object. Therefore, this is prevented from running there by looking for the presence of the window object again: this.allowPolling = (typeof window !== 'undefined');

The fetching of new data doesn’t happen here. Once the timer expires an event is dispatched to the store, which will make a fetch for new data and dispatch a separate event with the results.

export const fetchLines = () => (dispatch) => {

dispatch(requestLinesUpdate());

return fetch(API_PATH_ALL)

.then(response => response.json())

.then((data) => {

saveLines(data);

dispatch(receiveLinesUpdate(data));

})

.catch(() => {

dispatch(receiveLinesUpdate(null));

});

};

The receiveLinesUpdate event triggers the BaseContainer to be re-rendered with the new data, as the incoming linesState prop has now changed.

Once the BaseContainer has its data it returns a <Layout> component with several props:

return (

<Layout

lines={this.props.lines}

appClass={appClass}

innerChildren={this.props.children}

warningMessage={<OutOfDateWarningContainer />}

/>

);

The <Layout> component is a simple function, rather than a full React component. It accepts the props provided as arguments, and so will be changed by the container when these arguments change. It simply uses this data to return a JSX representation of the HTML required:

const Layout = ({ innerChildren, lines, appClass, warningMessage }) => (

<div className={appClass}>

<div className="app__main">

<div className="app__header header">

<header>

<div className="header__logo">

<Link to="/">TubeAlert</Link>

...

Any container could use this component, as long as it sets the props as required. As this is the wrapping layout, it contains an innerChildren argument, which will be the Container for the individual page types.

The LineContainer handles pages at /:line URLs, such as /bakerloo-line and /circle-line. The source of data for the line is available in the store state linesState object, so that just has to be filtered to the line in question.

export default connect(

(state, props) => ({

line: state.linesState.lines.find(line => line.urlKey === props.params.lineKey)

})

)(LineContainer);

The props.params.lineKey comes from the routing, and is used to find the line required. The Line page has the Subscriptions panel, which has its own Container. There is quite a lot of logic in this container, as it handles the process of displaying and updating subscriptions.

The subscriptions panel is a table of day columns with row hours. Each cell contains a checkbox to indicate if that hour should be part of the subscription. TubeAlert always makes use of standard elements such as <a>, <input>, <label> and <button>, rather than handling clicks on <div> or <span> elements. This is because the browsers already have stable behaviour on these elements so keyboard support and most accessibility support comes for free.

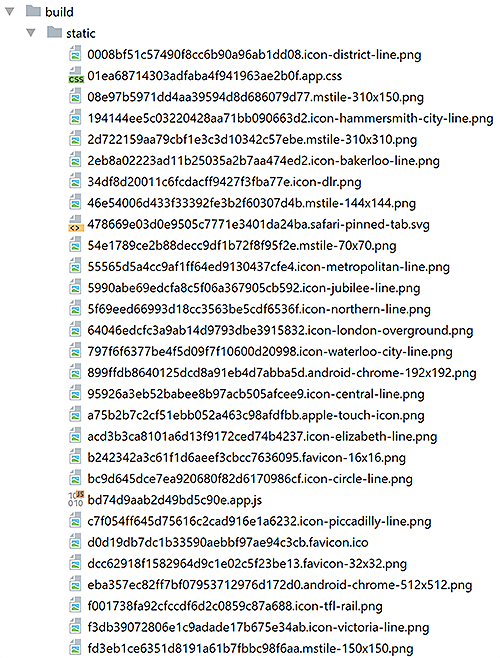

Static assets

When loading in the browser the webpage will need to load the JavaScript application. It will also need to load the CSS and any images. In order to do this it needs to know where to find them. They are going to be placed on a separate subdomain: https://static.tubealert.co.uk

S3 Bucket setup

Cloudflare is setup in front of https://static.tubealert.co.uk to provide caching and HTTPS support. In order to support this the bucket name must be the same as the domain. Therefore the bucket is created as such and the Cloudflare DNS sets up a CNAME as an alias to static.tubealert.co.uk.s3-website.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com.

The bucket itself is setup via the Resources section of the serverless.yml config. This is simply Cloudformation config.

CORS is activated on the bucket to allow the front end application (particularly the service worker) to be able to access these assets.

CorsConfiguration:

CorsRules:

- AllowedMethods:

- 'GET'

AllowedOrigins: ['*']

AllowedHeaders: ['*']

AWS recommend that your naming structure of files in your bucket is as spread/random as possible. This is because the files are partitioned to different servers according to filename. If all your files are similar in filename then you risk all your requests coming from the same server which can result in lower performance. A “folder” in S3 is only virtual so it is part of the filename. For this reason our static bucket will not have any folders. It’s unlikely TubeAlert will reach the level of traffic that this becomes a concern, but it is a good practice habit to follow.

We want the static files to be cached for a long time (1 year), so the filename contains the hash of the contents. If the contents change then the filename will change. It also solves the AWS sharding recommendations by putting this hash at the front.

2bd9189224077b82ec06.app.js

01ea68714303adfaba4f941963ae2b0f.app.css

Over time this could mean the S3 bucket gets full of many files and it might not be clear which ones are still in use and which ones aren’t. Therefore the bucket has been setup with an expiry policy.

LifecycleConfiguration:

Rules:

- Id: S3ExpireMonthly

ExpirationInDays: 30

Status: Enabled

This deletes any files that are older than one month, so we will need to make sure we redeploy the files still in use and reset their one month clock before that expires.

CSS & Images

Sass (SCSS) is used to add structure to building the CSS. BEM is used as a naming strategy, and it is broken up into discrete components using Atomic Design principles

In order to have the Sass built into CSS it must be included in the webpack entry point client.js

import '../src/scss/all.scss';

Notice here how it pulls in all.scss, which in turn pulls in the other Sass components. It can be written so that each React component imports the Sass relevant to itself only, but this became unwieldy to manage and wasn’t compatible with server-side rendering. This way only the client entry point knows about the Sass. By default webpack will embed the resulting CSS into the JavaScript, but we want the application to function without JavaScript so we force a separate file:

config.plugins.push(

new ExtractTextPlugin('[contenthash].[name].css')

);

Images also need to be processed by webpack, so that they get a hashed filename. Similar to the Sass, they need to be imported into the client.js:

import '../src/imgs';

This pulls in the imgs/index.js file, which is then responsible for importing all images in the imgs folder that the application needs.

The resulting set of images and CSS is created in the build/static folder under their hashed names.

Manifest file

The hashing of the filename can be set using webpack (e.g config.output.filename ='[chunkhash].[name].js'; for JavaScript). In order to know where to find those files we need a lookup list so we instruct webpack to build a manifest file.

new ManifestPlugin({

fileName : '../assets-manifest.json'

})

Any references to these files within our application/css, will automatically be recognised by webpack, but our surrounding HTML will need to know the full paths and so will use this manifest file.

Unhashed files

The hashed filenames will be able to be cached for a year, as references to them will be updated if anything changes in them. But there are a few files that need predictable filenames, and should not be cached for that long. These are:

- browserconfig.xml (used in Windows to display a tile in the Start menu)

- manifest.json (used in Android to support adding to homescreen and loading like an app)

- sw.js (the service worker for offline and push notifications)

Each of these references some of the hashed files, so needs to be parsed by webpack in order to get their true path. Therefore they are placed in a templates folder and imports are included inline, such as

"src": "<%= require('../../imgs/android-chrome-512x512.png') %>",

Webpack can parse these and put the result in the build folder (in a separate static-low-cache location):

new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

template: path.resolve(__dirname, '../src/webapp/templates/manifest.json'),

filename: '../static-low-cache/manifest.json',

inject: false

})

The sw.js file is handled differently. The service worker (which we’ll discuss more later) will need the full list of assets from the assets-manifest.json in order to cache them. Therefore it will have to import that file. In order to do this the service worker sw.js is used as another webpack entry point with the following at the top:

const assetManifest = require('../build/assets-manifest.json');

Items in the build directory are now ready to be uploaded to S3.

Webpack files

Webpack can be set up in various ways. Based on all the needs for the TubeAlert infrastructure we have identified there are four webpack configs required. There is also a webpack.base.config.js which several of them inherit from (to save repeating the same options every time). The main shared portions of config are to setup Sass, and Babel so that ES2015 class structure and imports can be used

webpack.dev.config.js

The webpack.dev file is used during development and is activated via yarn dev, or to provide a server yarn server. The server makes use of the built in webpack dev server to offer hot reloading during development. This is needed for convenient development of the React application

webpack.prod.config.js

The webpack.prod file is activated via yarn prod. It is run during the build and generates the application JavaScript and CSS. This uses production mode for react and minifies the output to reduce filesize. It creates files in the build folder, named by hash and ready for upload to the S3 static location.

webpack.build.config.js

The lambda function for the webapp is running in Node 6, which cannot understand ES2015 imports or JSX syntax natively. Therefore the webpack.build webpack file builds the app.js for the lambda function and puts it in the build folder (not hashed). It has a different entry point to the client side version of the application as it needs to return a html response rather than activate a DOM element. This also runs ESLint and will fail the build if there are any issues.

webpack.sw.config.js

The webpack.sw file simply builds the service worker. The service worker needs to know the hashed address of the static assets in order to cache them, so this webpack method will embed the manifest file (generated from webpack.prod.config.js) into the service worker itself. As the hash for the assets will be different when there are changes this also means the service worker will update due to the embedded manifest value now having different values.

Deployment pipeline

TubeAlert is using Travis for the build and deployment process. Setting up Travis is done through the .travis.yml file. We want Travis to run the tests to check everything ok. If that is successful it should deploy the Lambda functions and push the static assets to S3.

First we want to make sure Travis has Serverless installed:

before_script:

- yarn global add serverless

Then there are several steps for Travis to run:

script:

- yarn install # Install dependencies and create the node_modules folder

- yarn test # Run the test suite (will stop if it fails)

- yarn build # Run webpack for server side build/app.js

- yarn prod # Run webpack for client side js, css and images

- yarn sw # Run webpack to create the service worker

- yarn install --production --ignore-scripts --prefer-offline # Clear dependencies only required for dev

- serverless deploy # Deploy all the lambda functions

After this has run the Lambda functions have all been updated. Next we need Travis to deploy the static assets to S3. Travis supports S3 deployment so we can set that up for the build/static folder:

deploy:

# Deploy the static assets (1 year lifetime)

- provider: s3

region: $AWS_REGION

access_key_id: $AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID

secret_access_key: $AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

bucket: $STATIC_BUCKET

skip_cleanup: true

acl: public_read

cache_control: "max-age=31536000"

local_dir: build/static

The required parameters such as $AWS_REGION are set in the Travis settings for the application.

Note, the cache_control setting is set for one year, so all files uploaded from the source folder (build/static) will be set to this. This is why we needed to put the unhashed files in their own separate folder. For those files we have a second set of deploy instructions, so they are only cached for 10 minutes:

# Deploy the static assets (10 mins lifetime)

- provider: s3

region: $AWS_REGION

access_key_id: $AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID

secret_access_key: $AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

bucket: $STATIC_BUCKET

skip_cleanup: true

acl: public_read

cache_control: "max-age=600"

local_dir: build/static-low-cache

At the end of this process, the application is successfully deployed.

You will remember we set the S3 bucket to expire files and delete them after 30 days. This is to ensure files no longer in use are cleaned up. Files that are redeployed will reset that clock, so in the Travis settings a cron job is set up to redeploy master every week. This gives the Travis build 4 chances before files are lost so any issues have plenty of time to alert and be fixed.

Making it a Progressive Web App

We’d like the application to be a progressive web app, allowing it to enhance so far as to work offline and be added to the homescreen like a native app can. However we’d like to take it further and ensure the application uses full progressive enhancement, so it works without any JavaScript at all. In order to do this it needs to support server side rendering.

Server side rendering

By rendering on the server the initial perceived performance of the website will always be better than a purely client side solution, as all the content is visible while the JavaScript is still loading and booting. In practice, as our “server” is actually a Lambda function, there is likely to be an initial latency as the function initialises.

The Lambda function handling the URLs arrives in the WebappController. This function renders the React webapp and returns a response.

In the Lambda function Node cannot understand JSX syntax, so we can’t enter the React application directly. The code is compiled (in webpack.build.config.js) through Babel and put into build/app.js which is imported into the controller

const App = require('../../build/app.js'); // Load the compiled App entry point

This webpack config uses a different entry point from the client.js. It uses build.jsx to handle the differences between browser and server.

The Controller already fetched the latest status from DynamoDb, so it passed it in as originalData

export default (originalData, location, assetsHelper, callback) => {

store.dispatch(setLines(originalData));

It is dispatched to the Redux store so it can be picked up by the deeper parts of the application. Next it needs to generate the result of the React application as a HTML string:

match({ routes, location }, (error, redirectLocation, renderProps) => {

const html = ReactDOMServer.renderToString(

<Provider store={store}>

<RouterContext {...renderProps} />

</Provider>

);

match is the React Router function that can recieve the incoming URL path (location) and the usual routes and provide the result as <RouterContext>. The result is wrapped in <Provider> so it has access to the Redux store. The rest of the application after route matching is exactly the same code as the client side, so true Universal JavaScript.

The result of this will be a string in html that is the HTML output of the application. This application is expecting to be rendered inside an element such as <div id="webapp"></div> but is missing all of the surrounding furniture needed to build a webpage (<head>,<body> etc), so this file is where we include that. The callback is called with the full body:

return callback(`<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-GB">

<head>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<title>TubeAlert</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="${assetsHelper.get('app.css')}" />

...

</head>

<body>

...

<div id="webapp">${html}</div>

<script src="${assetsHelper.get('app.js')}"

data-lines="${JSON.stringify(originalData).replace(/"/g, '"')}" id="js-app-bundle"></script>

...

</body>

</html>`

The assetsHelper was passed in from the WebappController and reads the assets-manifest.json to find the fulled hashed path of the desired CSS and JavaScript (so that the client side version of the app loads).

The output of the application is put inside the <div id="webapp"> element (which is where the client side version is expecting to find it and replace it).

Notice how the <script> includes a data-lines property with the full line status data. This was used by the client side script on boot to allow it to render without having to go and make a separate call for data.

Service Worker

Using a Service Worker we can make TubeAlert work offline and support push notifications. Service Workers can be quite powerful, so they are restricted in how they can run. First, they have to be served from HTTPS websites. TubeAlert is behind CloudFlare, to facilitate caching and HTTPS on all assets. They also need to be served from the same domain that they are controlling. Therefore, it cannot be served from https://static.tubealert.co.uk like the other static assets (even though it exists there after the build). It also cannot have a hashed filename, as browsers will recheck the same file for changes in order to decide when to update. If we had a hashed file name the browser would never find changes.

Service worker API Gateway proxy

Even though the file is available on S3 (https://static.tubealert.co.uk/sw.js) it cannot be served from there as the main site is https://tubealert.co.uk. A new API gateway route is setup to be a proxy to that file on S3. In our Serverless Resources section we can have a CloudFormation template that sets up the appropriate IAM permissions to give API Gateway permissions to access the StaticBucket on S3:

APIRole:

Type: AWS::IAM::Role

Properties:

Policies:

- PolicyName: 'ServiceWorkerAPI'

PolicyDocument:

Statement:

- Effect: 'Allow'

Action:

- 's3:GetObject'

Resource:

- Fn::Join:

- ''

- - 'arn:aws:s3:::'

- Ref: StaticBucket

- '/sw.js'

AssumeRolePolicyDocument: